Autism parents put a million details into the care of their beloved children. But what will happen when those parents are gone?

Read moreHow a simple vest made everything better

“I hear so many words of appreciation from those using the Vests, but also from those wanting a better understanding of autism. It is heartening.”

Read moreHow Many Broken Bones Is Enough?

By Duane Sloane

The worst is the passive aggressive guilt placed on parents when they become so overwhelmed they can no longer handle their child at home.

To those who may be among those who judge let me ask you: How many broken bones is ok? How many times should it be ok to be punched, pinched, purposefully vomited on?

How long should the siblings not be ever able to have friends over or sleep through the night? What’s the cutoff number for punching your six year-old brother?

Is there any PTSD involved for the rest of the family? How about the 11 year-old sister who is just used to the idea that her 16 year-old brother randomly strips naked and walks around naked, sometimes with an erection before we see him?

I contend that there are more selfish things than residential care. Like a lifetime of scars for everyone else to deal with as well. A fully staffed, well run residential facility is not a punishment to our children. It’s a decision filled with guilt and self-doubt.

But for those truly severe and beyond the cute toddler stage it is a heart wrenching sometimes necessary decision. Unless you have dealt day-to-day with violent severe autism in an adolescent, maybe reserve judgment. In fact just reserve judgment regardless.

There’s enough guilt already.

Severe Autism Needs "Institutions"

Severe Autism Needs “Institutions”

“Institution” can mean: “a facility where disabled people live in a confined setting, segregated from society, and without consent.”

But “institution” can also mean: “an organization that serves an important public purpose or societal need.”

Harvard is an “institution”

The YMCA is an “institution”

Mayo Clinic is an “institution”

St. Jude’s Hospital is an “institution”

The local high school is an “institution”

Those who attack autism-serving programs as “institutions” are not really anti-institution. They are just invoking a bogeyman to de-fund your essential disability services.

Don’t be fooled. High-quality “institutions” (the second type) devoted to the well being of the severely autistic —whether providing day programs, housing or medical care, whether in the “community” or in their own buildings, whether small or big — are exactly what we need.

NCSA Public Comment for IACC Meeting, July 2021

After a two-year hiatus, the federal Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee is set to meet later this month. As a public comment NCSA submitted the following letter (here as a PDF).

Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee

National Institute of Mental Health

Via email: IACCPublicInquiries@mail.nih.gov

Re: Priorities for the federal response to autism

July 1, 2021

To the IACC members:

The National Council on Severe Autism, an advocacy organization representing the interests of individuals and families affected by severe forms of autism and related disorders, thanks you for your service to the IACC in effectuating the congressional mandate to further federally funded autism-related research and programs, and ultimately improve prospects for prevention, treatment and services.

Dramatically increasing numbers of U.S. children are diagnosed with — and disabled by — autism spectrum disorders. In the segment we represent, those children grow into adults incapable of caring for themselves and require continuous or near-continuous, lifelong services, supports, and supervision. Individuals in this category exhibit some or all of these features:

ï Nonverbal or have limited use of language

ï Intellectual impairment

ï Lack of abstract thought

ï Strikingly impaired adaptive skills

ï Aggression

ï Self-injury

ï Disruptive vocalizations

ï Property destruction

ï Elopement

ï Anxiety

ï Sensory processing dysfunction

ï Sleeplessness

ï Pica

ï Co-morbidities such as seizures, mental illness, and gastrointestinal distress

Given the immense and growing burden on individuals, families, schools, social services and medical care, the autism crisis warrants the strongest possible federal response. Parents are panicked about the future. Siblings are often terrified about having children of their own, and/or the burden of providing lifelong care for their very much loved but highly challenging brothers and sisters. Schools cannot recruit enough teachers and staff to keep up with growing demand. Adult programs and group homes refuse to take severe cases. Vastly more must be done to both understand the roots of this still-mysterious neurodevelopmental disorder and to prepare our country for the tsunami of young adults who will need care throughout their lifetimes, particularly as their caring and devoted parents age and pass away.

With that in mind, we ask the members of the IACC to understand the priorities of our community. While this list is not exhaustive it represents many of the issues our families consider most urgent.

In the course of committee deliberations:

The amorphous word “autism” should never obscure the galactic differences among people given this diagnosis. The construct of “autism” — and it is just that, an artificial human invention contorted by political and historical forces — has thrown together into one bucket abnormal clinical presentations that often have nothing in common. A person in possession of intact cognitive abilities and/or adaptive functioning who suffers from social anxiety and sensory processing differences has no meaningful overlap with a person with severe intellectual impairment, little to no adaptive skills, and aggressive behaviors. The IACC should take care to make distinctions at every juncture where “autism” is invoked in a general way.

Zero tolerance for anti-parent prejudice. It has been alarming to witness the re-emergence of parent-blaming in some sectors of the autism community. Parents provide the lion’s share of support for both children and adults with autism and have been at the forefront of reforms aimed at improving the lives of those disabled by autism. Parents also most reliably speak out on behalf of the best interests of their non- or minimally verbal children. We ask that the attitude of the IACC be one of zero tolerance for the disturbing trend of anti-parent prejudice.

Honest language to communicate realities. It is crucial that discussions at the federal level retain the language the reflects our clinical and daily realities, such as the following examples we commonly hear from our families and practitioners: abnormal, maladaptive, catastrophic, chaos, low-functioning, suffering, devastating, panicked, hopeless, desperate, exhaustion, overwhelming, anguish, traumatic, bankrupting, financially crushing, suicidal, epidemic, tsunami. We stress this not to detract from the many positives found in every person disabled by autism, of course those also exist, but to ensure that the challenges of autism are never semantically erased.

As federal priorities are developed:

The ever-increasing prevalence of autism must be treated with the utmost gravity. Rates of autism that meet a strict definition of developmental disability have soared 40-fold in California over the past three decades. Rates of autism now exceed 7% in some school districts in New Jersey. There is overwhelming evidence for growing rates of disabling autism, and little evidence this has been caused by non-etiologic factors such as diagnostic shifts. We have both a pragmatic and moral duty to discover the factors driving this alarming, unprecedented surge in neurodevelopmental disorders among our youth and young adults. Clearly, vaccines and postnatal events are not responsible for the surge in autism, but many other factors warrant urgent attention so we can finally “bend the curve” of autism.

Maximizing the range of options available to our disabled children and adults. We need a broad range of educational, vocational and residential services to meet the very diverse needs and preferences of the autism population — and this includes specialized and disability-specific settings that are are equipped to handle the intensive needs posed by severe autism. The post-21services “cliff” is a gut-punching reality across our country. Lack of non-competitive employment options. Lack of day programs. Few or no housing options. No HUD vouchers. Little to no crisis care. A healthcare system and ERs utterly unprepared for this challenging population. Aging parents. Lack of direct support providers. Lack of agencies willing to take hard cases. All of this amounts to a nightmare for our individuals and families. Clearly, massive policy changes are needed across multiple domains to maximize options for this growing population.

A desperate need for treatments. Regrettably, the therapeutic toolbox we have today is largely the same as two decades ago. While a cure for autism is unlikely to ever arise owing to the early developmental nature of the disorder, the IACC should push for research on potential therapeutics that can mitigate distressing symptoms such as aggression, self-injury, anxiety, insomnia, and therefore improve quality of life while decreasing the costs and intensities of supports. The research may include medical treatments such as psychopharmaceuticals, cannabis products, TMS, and others, as well as non-medical approaches.

We appreciate this committee’s commitment to autism prevention, treatment and services, and for your consideration of our community’s priorities.

Very truly yours,

Jill Escher

President

NCSA Publishes Position Statement on Facilitated Communication

Below is the text of a new Position Statement published by the National Council on Severe Autism urging caution with respect to the authenticity of communications generated via the use of “facilitated” techniques. NCSA strongly supports the wide variety of independent communication efforts by all with autism but is concerned about the rising popularity of several non evidence-based modalities that depend on the support of an intermediary to generate output. For more information regarding Facilitated Communication and related approaches, in addition to evidence-based practices, please review our recent webinar on the topic here.

NCSA Position Statement on Facilitated Communication

NCSA enthusiastically supports efforts to improve independent communication by all those with severe autism, whether the communication is verbal, gestural, written, or through devices such as Alternative and Assistive Communication (AAC) technologies or a keyboard. We cannot support, however, a technique known as Facilitated Communication (FC). The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) defines FC as “a technique that involves a person with a disability pointing to letters, pictures, or objects on a keyboard or on a communication board, typically with physical support from a ‘facilitator.’” This support can take the form of touching the body directly (typically the hand, wrist, elbow or shoulder) or merely holding the letterboard. Studies dating back to the 1990s have repeatedly demonstrated that the products of FC reflect the (often non-conscious) control of the facilitator and do not represent authentic communication by the disabled person. At times, false statements generated by FC practitioners have resulted in devastating outcomes, including false accusations of abuse against parents and others.

For these reasons, NCSA joins ASHA, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, the American Psychological Association, the Association for Science in Autism Treatment and over a dozen other national and international organizations in opposing the use of FC.

We also urge caution with regard to newer variants of FC such as the Rapid Prompting Method (RPM) and Spelling to Communicate (S2C). Like FC, these methods rely on the intervention of a partner to facilitate the communication, and therefore carry the risk of conscious or unconscious prompting by the intermediary. Although practitioners regularly contend the output is the independent work of the persons being facilitated, we are concerned that to date no reliable research has confirmed the authenticity of the communications and that practitioners have systematically resisted calls for simple, straightforward verification studies. Such studies would include message-passing tests, where the disabled person is asked to produce information or answer questions the facilitator does not know the answers to, or tests where the facilitator was blinded. While NCSA does not oppose advances in any therapeutic field, we also ask that such advances be evidence-based, and subject to reasonable scientific scrutiny, especially given the tragic history of dangerous and ineffectual interventions of the past, including FC.

Recently, advocates have begun conducting and publishing studies that claim to prove the legitimacy of letter boarding with technologies such as eye-tracking devices, accelerometers, and electroencephalography (EEG). Orthodox speech and language researchers consider the use of such elaborate and marginally relevant technologies a distraction from the fact that practitioners refuse to submit RPM and S2C to basic validity testing. They are also concerned about advocates’ claims that autism is a motor, not cognitive, disorder, which has no support in the research literature, and that people with autism have normal cognition but suffer from short-term memory loss precluding them from participating in such tests.

Additionally, autistic voices are frequently cited as valid sources of representation for use in scientific research and policy development on the federal, state and local levels. However, some of the voices that are alleged to be representative of autistics are actually facilitated through RPM or FC, and should not be presumed valid.

References:

In-depth analysis of FC literature: www.facilitatedcommunication.org.

American Speech Language Hearing Association, Facilitated Communication and Rapid Prompting Method: CEB Position

https://www.asha.org/ce/for-providers/facilitated-communication-and-rapid-prompting-method-ceb-position/

Donvan J, Zucker C. In a Different Key. 2016 Crown Publishers, New York. (See Chapters 33, 34 documenting past abuses of FC.)

Fein D, Kamio Y. Commentary on The Reason I Jump by Naoki Higashida. J. Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics2014;33(8):539-542. (Here, paywalled but first page is available.)

Mostert M. Facilitated communication since 1995: a review of published studies. J Autism Developmental Disord. 2001;31:287–313. (The abstract reads: “Previous reviews of Facilitated Communication (FC) studies have clearly established that proponents' claims are largely unsubstantiated and that using FC as an intervention for communicatively impaired or noncommunicative individuals is not recommended. However, while FC is less prominent than in the recent past, investigations of the technique's efficacy continue. This review examines published FC studies since the previous major reviews by Jacobson, Mulick, and Schwartz (1995) and Simpson and Myles (1995a). Findings support the conclusions of previous reviews. Furthermore, this review critiques and discounts the claims of two studies purporting to offer empirical evidence of FC efficacy using control procedures.”)

Schlosser RW et al. Rapid Prompting Method and Autism Spectrum Disorder: Systematic Review Exposes Lack of Evidence. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-019-00175-w. (The abstract reads: “This systematic review is aimed at examining the effectiveness of the rapid prompting method (RPM) for enhancing motor, speech, language, and communication and for decreasing problem behaviors in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). A multi-faceted search strategy was carried out. A range of participant and study variables and risk and bias indicators were identified for data extraction. RPM had to be evaluated as an intervention using a research design capable of empirical demonstration of RPM’s effects. No studies met the inclusion criteria, resulting in an empty review that documents a meaningful knowledge gap. Controlled trials of RPM are warranted. Given the striking similarities between RPM and Facilitated Communication, research that examines the authorship of RPM-produced messages needs to be conducted.”)

Adopted by NCSA Board of Directors, June 24, 2021

“My 22 Year-old Daughter with Severe Autism Improved After an Experimental Treatment”

Madison during one of her therapy sessions.

NCSA interview with an autism mom about her daughter’s experience with transcranial magnetic stimulation

Background

In February 2019, NCSA published a blogpost called, "Autism: Miswiring and Misfiring in the Cerebral Cortex," by Manuel Casanova, MD. He explained the evidence that autism can be rooted in pathologies of brain development, specifically abnormal micro-structural development of the “minicolumns” of the cerebral cortex, and further that this physiological defect had potential implications for therapeutics.

Dr. Casanova discussed that the cerebral cortex is the part of the brain that enables us to process sensory information, engage in complex thought and abstract reasoning, and produce and understand language. It accounts for our volitional actions including those that allow us to adapt to our immediate environment. But in autism we see the failure of connections — cells in the cerebral cortex are not able to coordinate their actions with other cells in their surroundings.

He then explained that these findings may suggest a therapeutic intervention based on transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). TMS works on the principle of induction of electricity. A strong magnetic field induces current through anatomical elements in the cerebral cortex that act as conductor. Due to the geometrical orientation of anatomical elements within the periphery of the cortical minicolumns, inhibitory elements are stimulated when using low frequency stimulation. This intervention allows us to rebuild the “shower curtain” surrounding the minicolumns.

He said that several hundred high functioning ASD patients have been treated with TMS with positive results, primarily in terms of improving executive functions and reducing perseveration.

This interview with autism mom Jan Kasahara is something of a follow-up to Dr. Casanova’s article. It is not meant to offer medical advice, and does not constitute an endorsement of this intervention. Rather, the purpose of this interview is to highlight the extremely urgent need for therapeutics for severe autism, and that this therapy may warrant greater scientific attention for low-functioning individuals.

Interview

NCSA: Jan, we wanted to give our community a chance to hear about your experience, because you have a daughter who has who is severely impacted by autism and who underwent this experimental treatment, which is very unusual. Please give us a bit of background about Madison.

JK: Madison is 22. We adopted her from China as a baby, and at the age of three she received a diagnosis of autism. She started talking and then stopped. She started hand flapping, spinning in circles, not wearing clothes, climbing on everything — pretty much showing many signs of low functioning autism. And since then, it's been a struggle to try and find something to help her.

She has severe OCD. She will hit her chin if she can't put all of her movies away. She will get upset in the car if we don’t go a certain direction. She would be constantly upset, often screaming, having trouble trying to show me what she wants. She can't point. She has trouble with tags on her clothes, she'll only wear crocs and won’t wear regular shoes. Very little eye contact and she can't really do anything functional, for example she can't brush her hair, she can't dress herself, she cannot help with anything around the house. She basically would sit on the couch and do YouTube all day or movies.

NCSA: Obviously one can see why a parent in your situation would be very eager to find something that could help her.

JK: I think the number one problem with her is language. I was really hoping to find something to help her achieve some form of language because I think that is a lot of her frustration. Also, she has a huge amount of anxiety, which was very, very high. She seemed like she'd always struggle with that or depression. She had no initiation. She didn't really care about people or what she was they were doing, so her quality of life was just so low. And I was just trying to think of anything that would help her quality of life.

NCSA: So what how did you come across the idea to try TMS?

JK: To be honest, I was on YouTube, and like any autism mom, trying to find anything that I could possibly find. And I fell upon a clinic based in San Mateo, which is not far from our home in the Bay Area. And there was also a little blurb about it from the TV show The Doctors about a young girl who had autism, and TMS helped her start speaking.

I am definitely one of those moms who is unafraid to experiment. So I researched it and spoke with the clinic’s director. So I met up with him and I felt really comfortable with him.

NCSA: To be clear, this treatment was not covered by insurance, just a private pay enterprise on your part.

JK: Our claim was denied but we are resubmitting it with more information. The six-week treatment was more than 10,000 dollars.

NCSA: Please tell us what the therapy consisted of, and any difficulties experienced by Madison.

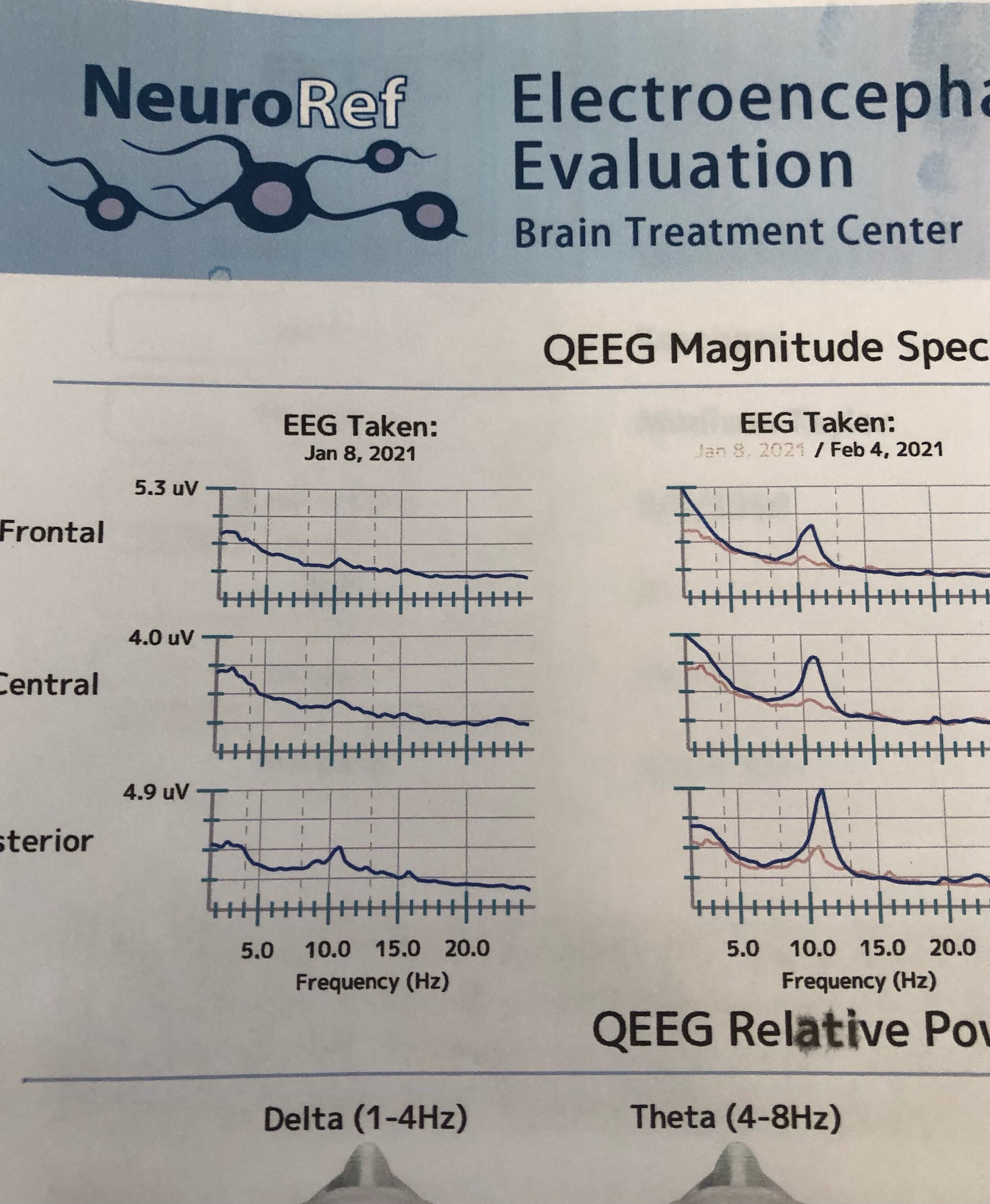

Well, first they need to do an EEG to look at her brainwaves to see more precisely what is going on. I’m hardly a neuroscientist but I’ve learned that with a lot of kids with autism, they find that their brain waves aren't functioning completely, which is associated with depression, anxiety, and insomnia. The waves are very flat.

In the EEG she had to wear a tight cap on her head with little electrodes. So we practiced at home, putting a bathing cap, shower cap and knitted beanie, anything to try and get her used to have something on her head. But once we got her in there, they were so sweet and they really made it easy for her. They need 10 minutes of quality data with her eyes closed, motionless and quiet. With Madison, the process took from 10 minutes to 40 minutes depending on how calm she was that day.

The EEG showed that basically her brain waves were pretty flat. He could tell also by looking at the brain waves that she wasn't sleeping, had a lot of depression and anxiety. The clinic had not worked with a lot of kids on the spectrum this severe, and they couldn’t promise anything regarding the treatment, but I decided to just go ahead. It was worth a try.

They developed a treatment plan based on the EEG, such as where they put the magnet, how strong they want to make it. In her case, they put it in the front part of the cortex and behind in the back of her head. The magnet is like a heavy, flat wand, with a handle and makes a clicking sound as they put it against the head to stimulate the brain.

It was of course challenging to keep Madison sitting still. I'm not going to say it was easy. She did get upset. The doctor actually made sure that he brought in Oreos, her favorite, to entice her to stay in the seat, which is like a leather recliner chair. They also have a weighted blanket and toys and would play movies and music videos. Some of the kids end up running down the halls and they just go retrieve them and bring them back and they really try their best.

NCSA: So how long did Madison have to sit in the chair for each session?

JK: About 30 minutes.

NCSA: Yeah, that would be hard for a lot of our kids. How many sessions did she do?

JK: So 30 minutes, five days a week for two weeks — that was the first set of sessions, and then we did two more sets. About 30 treatments altogether.

NCSA: But as you said, you’re a mom who is willing to try almost anything, you’re taking one for the team. So did you notice any changes in Madison right off the bat?

JK: It seemed like her anxiety did go down. I noticed that she was a lot calmer and she seemed more affectionate, which was something different. She was actually cuddling with me on the couch, which she had not really done before, and she was looking into my eyes more. She didn't seem as fearful like she was. So those were the main things in the very beginning. A lot of the fear, a lot of the depression and anxiety had seemed to go down and she seemed to be more affectionate.

NCSA: Then after the three sets of treatments?

The treatments ended in March and now we’re in June. I noticed her speech started getting a little bit clearer, including some new words. One night we were in her bedroom and I would hold up a book and she said “book.” And then I would hold something else like a bear, and she'd say, “bear.” It was so exciting, and she was just so fun. She was so happy.

She seemed to have more initiative. She had gone into the bathroom and I noticed that she'd taken the toothpaste and put it on her toothbrush, something she had never done, and she started brushing her teeth back and forth. So even her motor planning got better. Before she would just bite her toothbrush, but I actually saw her brushing back and forth. Then she'd take a hairbrush out and she'd start brushing her hair. That was just too much. That was something she would never do. So I could see that there was a lot of initiative happening. And that was very exciting.

I took her to the store yesterday and I thought to myself, she's not rocking back and forth on her feet like she normally does. She’s normally stimming with her hands, making all kinds of echolalia, walking into people. And she was just standing there, calm. It was so strange.

Recently she got all the dolls out of the garage. She had never played with dolls before. She brought them into the family room and she started pretend play. She started brushing their hair and changing their clothes and went and got the bed and put them in the bed - without anybody prompting her.

At school, they've told me they can't believe how great she's doing. She's not running into other classrooms like she always did. She's staying in the classroom. She's actually helping wash the dishes, which she's never done. She can ride the bike. She used to scream for somebody to help her get on the bike, but now she just gets on the bike by herself and goes. She doesn't scream anymore.

NCSA: The reason we wanted to publish something about your experience is not to make any claims about the treatment (this is classic n=1) but to stress that for kids like ours the need for progress is so urgent — we desperately need to find interventions that can increase functional capacity, improve quality of life, alleviate terrible symptoms. We need a more intensive research effort to find valid interventions.

JK: Absolutely! Our kids are suffering every day. They are behind a wall where they can't even express for themselves what's going on. They're depressed. They are dealing with trying to move their bodies and their bodies won't do what they want to do. They're hitting themselves. They're impulsive. These are kids who are going to need immense amount of help in the future. And if we can't find help for our kids, they're going to have a terrible life. They're going to suffer, and the last thing we want for our children. More and more kids have an autism diagnosis. The need to help them is absolutely desperate.

Changes in Madison’s EEG seen after a month of treatments.

NCSA: Did Madison’s EEG change after the treatment?

JK: Yes her EEG did change. The brain waves increased. So there seems to be an objective measure of improvement and not just our anecdotal observations.

NCSA: I wonder if the benefits you are seeing will be lasting.

JK: We don’t know. We shall see.

NCSA: Jan, thanks so much for taking the time to share your experience with our NCSA community.

_______

For further reading:

Casanova MF, Shaban M, Ghazal M, El-Baz AS, Casanova EL, Sokhadze EM. Ringing decay of gamma oscillations and transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy in autism spectrum disorder. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2021 Jun;46(2):161-73.

Casanova MF, Shaban M, Ghazal M, El-Baz AS, Casanova EL, Opris I, Sokhadze EM. Effects of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Therapy on Evoked and Induced Gamma Oscillations in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Sciences. 2020 Jul;10(7):423.

Casanova MF, Sokhadze E, Opris I, Wang Y, Li X. Autism spectrum disorders: linking neuropathological findings to treatment with transcranial magnetic stimulation. Acta Paediatrica. 2015 Apr;104(4):346-55.

Robison, John. Blogpost: TMS and Autism. http://jerobison.blogspot.com/p/use-of-tms-transcranial-magnetic.html

Disclaimer: Blogposts on the NCSA blog represent the opinions of the individual authors and not necessarily the views or positions of the NCSA or its board of directors.

NCSA Letter in Support of NJ Bill Allowing for Videocameras in Group Homes

New Jersey state capitol.

New Jersey State Senator Vin Gopal

New Jersey State Senator Stephen M. Sweeney

New Jersey Assemblymember Craig Coughlin

New Jersey Assemblymember Joann Downey

Via email to: sengopal@njleg.org, sensweeney@njleg.org, aswdowney@njleg.org, asmcoughlin@njleg.org

June 11, 2020

Re: Support for Billy Cray’s Law, Bill NJ A4013

Dear Senator Gopal, Senator Sweeney, Assemblymember Coughlin and Assemblymember Downey,

The National Council on Severe Autism (NCSA) has followed with great interest and fully supports Billy Cray’s Law, Bill NJ A4013, the effort in New Jersey to provide for electronic monitoring devices (EMDs) in group homes serving adults with developmental disabilities, including autism.

NCSA is a voice for the disabled who have no voice — specifically, the growing population of Americans disabled by severe forms of autism. Those with severe autism often have minimal language, low cognitive ability, severe functional impairments, and dangerous behaviors, including aggression, self-injury and property destruction. They typically need 24/7 care, for life, having little capacity to care for themselves or earn a living.

Tragically, one issue too often seen in our care system is neglect and abuse in group homes and other settings. Prevention of abuse and neglect, in addition to ensuring proper procedures and accountability, requires a multi-pronged approach including adequate hiring, training, pay, and supervision practices by all agencies responsible for the care of adults with autism/DD. One element of a healthy training and supervision practice is the use of EMDs in common areas with the approval of the home clients, and in private areas with approval of the individual resident. Normally, EMDs would not be necessary inside of residences, but one clear exception to that rule is the case of residents with impaired ability to communicate or advocate for themselves. In those cases, visual documentation compensates for the absence of information that could be gleaned from the client.

The benefit is three-fold: first, it would significantly enhance abuse and neglect prevention strategies as a training tool and a mechanism for instructive feedback for staff. Second it would help deter any neglectful or abusive behavior on the part of staff, and render programs generally more accountable to clients and their guardians. It would also assist in providing evidence in those cases where abuse or neglect is suspected, again, compensating for the fact that the minimally or nonverbal clients are incapable of communicating their circumstances and remain utterly dependent on others for their protection.

The bill strikes an important balance between protecting people's privacy and protecting their overall well-being. EMDs would be installed only upon consensus of clients, and in private rooms, only upon request of the residents. The recordings are retained by the group home for only a period of 45 days. Staff members would need to provide express written consent to the use of the EMDs in the group home's common areas, as a condition of the person's employment. A prominent written notice would be posted at the entrance and exit doors to the home informing visitors that they will be subject to electronic video monitoring while present in the home. The Department of Human Services would conduct on-site device inspections. The Ombudsman for Individuals with Intellectual or Developmental Disabilities and Their Families, the New Jersey Council on Developmental Disabilities, and the group home provider community, will work together to establish and publish guidelines for the development of internal policies.

Billy Cray’s Law is a very welcome addition to a developmental disability system that desperately needs more safeguards for vulnerable clients. Thank you for your commitment to the welfare of adults with severe disabilities and your consideration of this important bill.

Very truly yours,

Jill Escher

President

New Jersey Bill Aims to Place Video Cameras in Group Homes

By Johanna Burke

In 2017, Billy Cray, a 33 year-old man with a developmental disability, was found dead in his bedroom in his New Jersey group home where he resided. There was no video to record what transpired, and no charges were ever made.

Last year, the Billy Cray Law, Bill NJ A4013, was introduced in the New Jersey Legislature which would provide certain requirements for the use of video cameras (without audio) in group homes for individuals with developmental disabilities who are 21 and over. This bill does not apply to children living in group homes under the age of 21.

This bill aims to strike an important balance between protecting people's privacy and protecting their overall well-being. It is intended to give residents, specifically those with severe behavioral issues, the opportunity to request the video cameras in their group home to ensure their safety and safe care by their staff. This bill will require group homes to install these cameras in common areas which includes entrances, living areas, dining areas, stairwells, and outdoor areas, at the request of their residents. It does not include bathroom areas.

Group home residents can request cameras in their private rooms as well. Any recordings in the group home's common areas are to be retained by the group home for a period of 45 days. Whenever a licensee who runs a group home receives notice about a complaint, allegation, or reported incident of abuse, neglect, or exploitation occurring within the group home, the licensee will forward this video to DDD (Division of Developmental Disabilities) for appropriate review, all the relevant footage recorded in the group home's common areas.

The summary and full text of the bill is below.

Johanna G. Burke Esq. is a special needs attorney and advocate based in Hawthorne, New Jersey. You can find her at www.jgburkelaw.com.

2020-2021 Regular Session

Bill Summary A4013

This bill would provide certain requirements in association with the use of electronic monitoring devices (EMDs) at group homes for individuals with developmental disabilities. An "EMD" is a camera or other electronic device that uses video, but not audio, recording capabilities to monitor the activities taking place in the area where the device is installed. The sponsor believes that it is imperative to enhance the quality of life of people with disabilities. Through this bill, the sponsor aims to make video monitoring technology more available in group home settings, taking great care to strike the important balance between protecting people's privacy and protecting their overall well-being. In so doing, the bill respects the rights of all individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities, placing a premium on their individuality and recognizing that different people have different needs and preferences. Scope of Bill The term "group home" is defined more broadly in this bill than it is in other laws. Specifically, the term is defined to mean a living arrangement that is licensed by the Division of Developmental Disabilities (DDD) in the Department of Human Services (DHS), and is operated in a residence or residences leased or owned by a licensee; which living arrangement either provides the opportunity for multiple adults with developmental disabilities to live together in a home, sharing in chores and the overall management of the residence, or provides the opportunity for a single adult with developmental disabilities and extreme behavioral difficulties to live more independently while receiving full-time care, and in which on-site staff provides supervision, training, or assistance, in a variety of forms and intensity, as required to assist the individual or individuals as they move toward independence. "Group home" does not include a living arrangement that is dedicated for use by children with developmental disabilities. The revised definition used in the bill makes it clear that this term not only includes facilities that house multiple persons with developmental disabilities, but also includes facilities that, while commonly referred to as supervised apartments, provide group home-style living for a single person who has developmental disabilities and particularly severe behavioral difficulties that prevent them from being housed in a group home with other disabled persons. The bill would require group homes, as defined thereunder, to install EMDs in the common areas, upon the agreement, request, and uniform consent of all residents. "Common areas" is defined to include entrances, living areas, dining areas, stairwells, and outdoor areas, but not bathroom areas. The bill would additionally require group homes to permit the installation and use of EMDs in the private rooms of group home residents. The bill is not intended to impose new requirements on those group home providers who already engage in electronic monitoring pursuant to an internal organizational policy. As a result, the bill includes a provision that grandfathers-in and exempts from the bill's provisions those group homes that have already installed, and are utilizing, EMDs as of the bill's effective date. Specifically, the bill provides that any such group home: 1) may continue to use previously installed electronic monitoring devices in accordance with the organization's written policies; 2) will not be required to remove the devices from service; and 3) will not be required to comply with the bill's consent requirements in order to continue utilizing the devices. However, to the extent that a group home's common areas or private rooms do not contain EMDs on the bill's effective date, the licensee will be required to comply with the bill when installing new EMDs in such unmonitored areas. The bill is intended to give residents - particularly those with severe behavioral difficulties - the right to request electronic monitoring in the group home, as necessary to ensure their safe care. The bill is not intended to impose new electronic monitoring requirements on providers that already engage in electronic monitoring; and it is not intended to require other group home providers to commence electronic monitoring, except in those cases where the residents have requested and agreed to such monitoring. Installation and Use of EMDs in Common Areas Under the bill's provisions, any group home that does not have EMDs already installed in the group home's common areas will be required to install EMDs in those common areas, upon the collective request of the residents and the residents' authorized representatives, if all of the residents of the group home and their authorized representatives agree to have such EMDs installed and expressly consent to the installation and use of such devices. A licensee will be prohibited from requiring the group home's current residents to consent to the installation and use of EMDs in the common areas as a condition of their continued residency in the group home. A licensee operating a group home that does not have EMDs already installed in the common areas will be required: 1) within six months after the group home adopts an internal electronic monitoring policy pursuant to the bill's provisions, to take affirmative action to determine whether the residents of the group home and their authorized representatives want and consent to have EMDs installed and used in the group home's common areas; and 2) annually provide written notice to all residents and their authorized representatives informing them of their right to request the installation and use of EMDs in the group home's common areas. The bill would require any group home that installs and uses EMDs in its common areas, pursuant to the agreement, request, and consent of the residents, to: 1) require each person employed by the group home to provide express written consent to the use of the EMDs in the group home's common areas, as a condition of the person's employment; 2) ensure that a prominent written notice is posted at the entrance and exit doors to the home informing visitors that they will be subject to electronic video monitoring while present in the home; and 3) ensure that, in the future, the group home only allows residence by those individuals who consent to the ongoing use of EMDs in the group home's common areas. The EMDs installed in a group home's common areas are to be unobstructed and recording at all times. Each licensee will be required to inspect the devices, and document the results of each inspection, on a weekly basis. The DHS will further be required to annually conduct an on-site device inspection, as part of its broader group home inspection authority, in order to ensure that the EMDs installed in a group home's common areas are functioning properly, as required by the bill. An individual's refusal to consent to the use of EMDs in a group home's common areas may not be used as a basis to prevent the timely placement of the individual in appropriate housing without surveillance. The bill would specify that nothing in the provisions of section 3, regarding the installation of EMDs in a group home's common areas, may be deemed to prohibit a group home licensee from installing and utilizing EMDs in the group home's common areas, pursuant to the group home's internal policies, in cases where the group home's residents have not submitted a collective request for such monitoring. This bill is intended to require the placement of EMDs in common areas only in cases where group home residents have collectively requested the electronic monitoring of such common areas. It is not intended to limit a licensee's discretionary ability to install and utilize EMDs in the common areas, in accordance with the group home's internal policies, in the absence of a collective resident request. Installation and Use of EMDs in Private Rooms The bill would further require all group homes to permit EMDs to be installed and used, on a voluntary and noncompulsory basis, in the private rooms of residents. The installation and use of EMDs in a private single occupancy room may be done by the resident or the resident's authorized representative, at any time, following the resident's provision of written notice to the licensee of the resident's intent to engage in electronic monitoring of the private room. Such written notice is to be submitted to the licensee at least 15 days prior to installation of the devices in the private single occupancy room. Any resident, or the authorized representative thereof, who provides such a notice of intent to install EMDs in a private single occupancy room, or who so installs such devices, will be deemed to have implicitly consented to electronic monitoring of the private room. The installation and use of EMDs in a private double occupancy room may be effectuated only with the express written consent of the roommates of the resident who requested the monitoring, or of the roommates' authorized representatives, as the case may be. A roommate may place conditions on his or her consent to the use of EMDs within the double occupancy room, including conditions that require the EMDs to be pointed away from the consenting roommate at all times during operation, or at certain specified times. The roommate's consent to electronic monitoring, and any conditions on the roommate's consent, are to be memorialized in a formal electronic monitoring agreement that is executed between the consenting roommate and the resident who requested the monitoring, or between their authorized representatives, as appropriate. The licensee, either through its own activities or through a third-party's activities, will be required to ensure that the conditions established in the agreement are followed. If a resident's roommate or the roommate's authorized representative, as appropriate, refuses to consent to the installation and use of an EMD in a private double occupancy room, or if the licensee is unable to ensure compliance with the conditions on such installation and use that are imposed by a consenting roommate or the roommate's authorized representative, the licensee will be required, within a reasonable period of time, and to the extent practicable, to transfer the resident requesting the installation of the device to a different private room, in order to accommodate the resident's request for private monitoring. If a request for private monitoring cannot be accommodated, the resident or resident's authorized representative may notify the DDD, which will be required to make every reasonable attempt to timely transfer the resident to a group home that can accommodate the request. All of the costs associated with installation and maintenance of an EMD in a private room are to be paid by the resident who requested the monitoring, or by the authorized representative thereof. Additional Provisions The bill would require a group home licensee, when seeking to obtain consent from residents for electronic monitoring, to comply with best practices that apply to professional interactions or communications being undertaken with persons with developmental disabilities, and particularly, with those persons who have difficulty with communication or understanding. The DDD would be authorized to impose any additional consent or consent declination requirements that it deems to be necessary. Any recordings produced by an EMD in a group home's common areas are to be retained by the group home for a period of 45 days. Any consent forms, consent declination forms, and notice of intent forms submitted under the bill are to be retained by the group home for a period of time to be determined by the DDD. Within 180 days after the bill's effective date, each group home will be required to develop and submit to the division a written internal policy specifying the procedures and protocols that are to be used by program staff when installing and utilizing EMDs. The internal policy is to provide, amongst other things, that whenever a licensee receives notice about a complaint, allegation, or reported incident of abuse, neglect, or exploitation occurring within the group home, the licensee will forward to the DDD, for appropriate review, all potentially relevant footage recorded by EMDs in the group home's common areas. Any residential program that fails to comply with the bill's requirements will be subject to a penalty of $5,000 for the first offense and $10,000 for the second or subsequent offense, as well as an appropriate administrative penalty, the amount of which is to be determined by the DHS. However, a group home licensee will not be subject to penalties or other disciplinary action for failing to comply with the bill's requirements if the group home licensee establishes, through documentation or otherwise, that EMDs were installed and being utilized in the group home on the bill's effective date, and that the group home is, therefore, exempt from compliance with the bill's provisions related to the placement of EMDs in unmonitored areas. The Commissioner of Human Services, in consultation with the assistant commissioner of the DDD, will be required to annually report to the Governor and Legislature on the implementation of the bill's provisions. The Ombudsman for Individuals with Intellectual or Developmental Disabilities and Their Families will similarly be required to include, in each of the ombudsman's annual reports, a section evaluating the implementation of the bill and providing recommendations for improvement. In addition, the bill requires the DDD, within five years of the bill's effective date, to submit a written report that: 1) identifies best practices for the installation and use of EMDs under the bill; 2) identifies best practices and provides recommendations regarding the obtaining of informed consent for electronic monitoring under the bill; and 3) provides recommendations for the implementation of new legislation, policies, protocols, and procedures related to the use of EMDs in group homes. This bill is named in honor of Billy Cray, an individual with a developmental disability who, in 2017, at 33 years of age, was unfortunately found dead in the group home in New Jersey where he resided.

Subject

Health, Human Services and Senior Citizens

Sponsors (2)

Senator Gopal and Senator Madden

Last Action

Introduced in the Senate, Referred to Senate Health, Human Services and Senior Citizens Committee (on 08/03/2020)

Full Text of Bill A4013

Be It Enacted by the Senate and General Assembly of the State of New Jersey:

1. This act shall be known, and may be cited, as "Billy Cray's Law."

2. As used in this act:

"Authorized representative" means a group home resident's court-appointed guardian of the person or, if there is no guardian of the person, the person who holds a valid power of attorney or is otherwise legally authorized to act as the representative of the group home resident for the purposes of making decisions related to the resident's care and living arrangements. "Authorized representative" does not include a caregiver or any other person who is employed or contracted, on a paid or unpaid basis, by the group home licensee.

"Common areas" means the living areas, dining areas, entrances, outdoor areas, stairwells, and any other areas within a group home, except bathrooms, which are commonly and communally accessible to all residents and are not dedicated for private use by a particular resident.

"Division" means the Division of Developmental Disabilities in the Department of Human Services.

"Electronic monitoring device" means a camera or other electronic device that uses video, but not audio, recording capabilities to monitor the activities taking place in the area where the device is installed.

"Group home" means a living arrangement that is licensed by the division and is operated in a residence or residences leased or owned by a licensee, which living arrangement either provides the opportunity for multiple adults with developmental disabilities to live together in a home, sharing in chores and the overall management of the residence, or provides the opportunity for a single adult with developmental disabilities and extreme behavioral difficulties to live more independently while receiving full-time care, and in which on-site staff provides supervision, training, or assistance, in a variety of forms and intensity, as required to assist the individual or individuals as they move toward independence. "Group home" does not include a living arrangement that is dedicated for use by children with developmental disabilities.

"Licensee" means an individual, partnership, or corporation that is licensed by the division and is responsible for providing services associated with the operation of a group home.

"Private room" means the private bedroom of a group home resident.

"Private single occupancy room" means a private room that is occupied by only a single group home resident.

"Private double occupancy room" means a private room that is occupied by two or more group home residents.

3. a. A group home that does not have electronic monitoring devices already installed in the group home's common areas shall be required to install electronic monitoring devices in those common areas, upon the collective request of the residents and the residents' authorized representatives, if all of the residents of the group home and their authorized representatives agree to have such electronic monitoring devices installed and expressly consent to the installation and use of such devices. A licensee shall not require current residents to consent to the installation and use of electronic monitoring devices in the common areas as a condition of their continued residency in the group home. Each licensee operating a group home that does not have electronic monitoring devices already installed in the common areas shall:

(1) within six months after the group home adopts an internal electronic monitoring policy pursuant to section 5 of this act, take affirmative action to determine whether the residents of the group home and their authorized representatives want and consent to have electronic monitoring devices installed and used in the group home's common areas pursuant to this section; and

(2) annually provide written notice to all residents and their authorized representatives informing them of their right to request the installation and use of electronic monitoring devices in the group home's common areas, as provided by this section.

b. A group home that installs and uses electronic monitoring devices in its common areas pursuant to the agreement, request, and consent of the residents, as provided by this section, shall:

(1) require each person employed by the group home to provide express written consent to the use of the electronic monitoring devices in the group home's common areas, as a condition of the person's employment;

(2) ensure that a prominent written notice is posted at the entrance and exit doors to the home informing visitors that they will be subject to electronic video monitoring while present in the home; and

(3) ensure that, in the future, the group home only allows residence by those individuals who consent to the ongoing use of electronic monitoring devices in the group home's common areas.

c. An individual's refusal to agree and consent to the use of electronic monitoring devices in a group home's common areas shall not be used as a basis to prevent the timely placement of the individual in appropriate housing without surveillance.

d. Any electronic monitoring devices installed pursuant to this section shall be unobstructed and recording at all times, and any recordings produced by the devices shall be retained by the program for a period of 45 days. Each licensee shall inspect the devices, and shall document the results of each inspection, on a weekly basis.

e. The Department of Human Services shall annually conduct an on-site device inspection at each group home in order to ensure that any electronic monitoring devices installed in the common areas are functioning properly, as required by subsection d. of this section. The department may elect to conduct the on-site device inspection required by this subsection as part of the broader inspection of each group home that it is required to perform under section 8 of P.L.2017, c.328 (C.30:11B-4.3).

f. Nothing in this section shall be deemed to prohibit a group home licensee from installing and utilizing electronic monitoring devices in the group home's common areas, pursuant to the group home's internal policies, in cases where the group home's residents have not submitted a collective request for such monitoring.

4. a. A group home for individuals with developmental disabilities shall permit electronic monitoring devices to be installed and used in a resident's private room, as provided by this section, for the purposes of monitoring the resident's in-room care, treatment, and living conditions. Each licensee shall:

(1) within six months after the effective date of this act, and annually thereafter, provide written notice to all residents, and to their authorized representatives, informing them of their right to install and use electronic monitoring devices in the residents' private rooms, as provided by this section, and articulating the notice requirements that are to be satisfied, pursuant to subsection b. of this section, before an electronic monitoring device may be installed and used in a private single occupancy room, and the consent requirements that are to be satisfied, pursuant to subsection c. of this section, before an electronic monitoring device may be installed and used in a private double occupancy room;

(2) ensure that reasonable accommodations are made, as necessary, to enable the authorized use of electronic monitoring devices in private rooms, as provided by this section; and

(3) provide written notice to the relevant resident, or the resident's authorized representative, of any applicable installation or building construction requirements or restrictions with which the resident must comply when installing and using an electronic monitoring device in the private room. Such notice shall be provided within 10 days after the licensee receives notice of the resident's intent to install electronic monitoring devices in a single occupancy room under subsection b. of this section or within 10 days after the licensee receives a resident's request for electronic monitoring of a double occupancy room under subsection c. of this section.

b. (1) The installation and use of electronic monitoring devices in a private single occupancy room: (a) shall be noncompulsory; and (b) may be done by the resident or the resident's authorized representative, at any time, following the resident's provision of notice to the licensee pursuant to paragraph (2) of this subsection.

(2) Any person who wishes to install and utilize electronic monitoring devices in a resident's private single occupancy room shall provide the licensee with a written notice of intent at least 15 days prior to installation of the devices, and shall comply with any installation or building construction constraints that are identified by the licensee in the notice that is provided to the resident pursuant to paragraph (3) of subsection a. of this section.

(3) Any resident who provides a notice of intent to install electronic monitoring devices in a private single occupancy room, or who so installs such devices, shall be deemed to have implicitly consented to electronic monitoring in the private room.

c. (1) The installation and use of electronic monitoring devices in a private double occupancy room shall: (a) be noncompulsory; (b) be conditioned upon the licensee's receipt of written consent to such monitoring from all roommates of the resident who is requesting the monitoring, or from the roommates' authorized representative, as appropriate; and (c) to the extent practicable, protect the privacy rights of all roommates of the resident who is requesting the monitoring.

(2) The roommate of a resident who requests electronic monitoring of a double occupancy room, or the roommate's authorized representative, may place conditions on his or her consent to the use of electronic monitoring devices within the private double occupancy room, including conditions that require the electronic monitoring devices to be pointed away from the consenting roommate at all times during operation or at certain specified times. The roommate's consent to electronic monitoring, and any conditions on a roommate's consent that are established pursuant to this paragraph, shall be memorialized in an electronic monitoring agreement that is executed between the consenting roommate and the resident who requested the monitoring, or between their authorized representatives, as appropriate. The licensee, either through its own activities, or through the activities of a third party, shall ensure that the conditions established in the agreement are followed.

(3) Each resident, or the authorized representative thereof, who wishes to install and use an electronic monitoring device in a double occupancy private room, shall file with the licensee: (a) a signed form, developed by the division, formally requesting and giving the resident's express consent for the installation and use of one or more electronic monitoring devices in the double occupancy room; and (b) a copy of the electronic monitoring agreement that has been executed between the resident and the resident's roommate pursuant to paragraph (2) of this subsection, or, if the roommate or the roommate's authorized representative has refused to consent to electronic monitoring of the private room, a copy of the consent declination form that has been signed by the roommate or the roommate's authorized representative.

(4) The installation and use of electronic monitoring devices in a private double occupancy room shall be done in compliance with any installation or building construction constraints that are identified by the licensee in the notice that is provided to the resident pursuant to paragraph (3) of subsection a. of this section.

d. If a resident's roommate or the roommate's authorized representative, as appropriate, refuses to consent to the installation and use of an electronic monitoring device in a private double occupancy room, or if the licensee is unable to ensure compliance with the conditions on such installation and use that are imposed by a consenting roommate or the roommate's authorized representative in the agreement executed pursuant to paragraph (2) of subsection c. of this section, the licensee shall, within a reasonable period of time, and to the extent practicable, transfer the resident requesting the installation of the device to a different private room in order to accommodate the resident's request for private monitoring. If a request for private monitoring cannot be accommodated, the resident or the resident's authorized representative may notify the division, in which case, the division shall make every reasonable attempt to timely transfer the resident to a group home that can accommodate the request.

e. A licensee shall not refuse to admit an individual to a group home, and shall not transfer or remove an individual from a group home, except as otherwise provided by subsection d. of this section, on the basis that the individual, or the individual's authorized representative, has requested electronic monitoring of the individual's private room, as authorized by this section.

f. A licensee shall ensure that a prominent written notice is posted on the entry door to any private room wherein electronic monitoring devices are installed and used pursuant to this section. The notice shall indicate that an electronic monitoring device has been installed in the room and that visitors will be subject to electronic video monitoring while present therein.

g. All of the costs associated with installation and maintenance of an electronic monitoring device in the private room of a resident shall be paid by the resident who requested the monitoring or by the authorized representative thereof.

5. a. (1) Within 90 days after the effective date of this act, the division, in consultation with the Ombudsman for Individuals with Intellectual or Developmental Disabilities and Their Families, the New Jersey Council on Developmental Disabilities, and the group home provider community, shall establish and publish guidelines for the development of internal policies pursuant to this section.

(2) Within 180 days after the publication of guidelines pursuant to paragraph (1) of this subsection, each licensee shall develop and submit to the division a written internal policy specifying the procedures and protocols that are to be used by facility staff when installing and utilizing electronic monitoring devices as provided by this act.

b. An internal electronic monitoring policy established pursuant to this section shall:

(1) describe the procedures and protocols that are to be used: (a) when obtaining consent from residents and facility staff for the use of electronic monitoring devices in a group home's common areas, as provided by section 3 of this act; and (b) when obtaining consent from residents and roommates for the use of electronic monitoring devices in a private double occupancy room, as provided by subsection c. of section 4 of this act;

(2) describe the procedures and protocols that are to be used in the review of footage recorded by electronic monitoring devices in the group home's common areas. The procedures and protocols adopted pursuant to this paragraph shall, at a minimum, reflect the requirements of subsection c. of this section; and

(3) identify the persons who will have access to footage recorded by electronic monitoring devices installed in the group home's common areas and private rooms, and the circumstances under which recorded footage will be subject to review by such persons.

c. Whenever a licensee receives notice about a complaint, allegation, or reported incident of abuse, neglect, or exploitation occurring within the group home, the licensee shall forward to the division, for appropriate review, all potentially relevant footage recorded by electronic monitoring devices in the group home's common areas.

6. a. The division shall:

(1) develop, and provide to each licensee, consent forms that are to be filled out and signed by individuals who consent to or request electronic monitoring under section 3 or subsection c. of section 4 of this act, and consent declination forms that are to be filled out and signed by individuals who refuse to consent to such electronic monitoring; and

(2) develop, and post on its Internet website, standardized notice of intent forms that a group home resident and the resident's authorized representative may elect to use when providing a licensee with a notice of intent to engage in electronic monitoring of a private single occupancy room, as required by subsection b. of section 4 of this act.

b. Consent forms and consent declination forms filed under section 3 or subsection c. of section 4 of this act and notices of intent filed under subsection b. of section 4 of this act shall be retained by the licensee for a period of time to be determined by the division.

c. When seeking to obtain consent from residents for electronic monitoring, as required by this act, a licensee shall comply with best practices that apply to professional interactions or communications being undertaken with persons with developmental disabilities and particularly, with those persons who have difficulty with communication or understanding.

d. The division may establish additional consent or consent declination requirements, for the purposes of this act, as deemed by the division to be necessary.

7. Notwithstanding the provisions of this act to the contrary, if, as of the effective date of this act, a licensee has already installed and is utilizing electronic monitoring devices in a group home's common areas or private rooms, the licensee: may continue to utilize the devices so installed, in accordance with the licensee's written internal policies; shall not be required to remove the devices from service; and shall not be required to comply with the provisions of this act in order to continue utilizing the previously-installed devices. However, to the extent that a group home's common areas or private rooms do not contain electronic monitoring devices on the effective date of this act, the licensee shall comply with the provisions of section 3 and 4 of this act, as applicable, when installing and utilizing new electronic monitoring devices in such unmonitored areas.

8. a. Any licensee that fails to comply with the provisions of this act shall be subject to a penalty of $5,000 for the first offense and a penalty of $10,000 for the second or subsequent offense, to be collected with costs in a summary proceeding pursuant to the "Penalty Enforcement Law of 1999," P.L.1999, c.274 (C.2A:58-10 et seq.), as well as an appropriate administrative penalty, the amount of which shall be determined by the division.

b. A group home licensee shall not be subject to penalties under this section, or to any other disciplinary action, for failing to comply with the requirements of section 3 or 4 of this act, as applicable, if the group home licensee establishes, through documentation or otherwise, that electronic monitoring devices were installed and being utilized in the group home's common areas or private rooms, or both, as of the effective date of this act, as provided by section 7 of this act, and that the group home is, therefore, exempt from compliance with the requirements of section 3 or section 4 of this act, as appropriate.

9. a. Within five years after the effective date of this act, the division shall prepare and submit to the Governor, and, pursuant to section 2 of P.L.1991, c.164 (C.52:14-19.1), to the Legislature, a written report that:

(1) identifies best practices for the installation and use of electronic monitoring devices under this act;

(2) identifies best practices and provides recommendations regarding the obtaining of informed consent for electronic monitoring, as provided by this act; and

(3) provides recommendations for the implementation of new legislation, policies, protocols, and procedures related to the use of electronic monitoring devices in group homes.

b. The Commissioner of Human Services, in consultation with the assistant commissioner of the division, shall annually prepare and submit to the Governor, and, pursuant to section 2 of P.L.1991, c.164 (C.52:14-19.1 et seq.), to the Legislature, a written report describing how this act has been implemented in the State. Each annual report shall include, at a minimum:

(1) a list of group homes that are currently using electronic monitoring devices in the common areas;

(2) a list of group homes that have not installed electronic monitoring devices in the common areas;

(3) to the extent known, a list of group homes that have failed to install and use electronic monitoring devices in the common areas upon the request of the residents, as provided by section 3 of this act, despite the licensee's receipt of uniform resident consent authorizing such monitoring, and an indication of the penalties that were imposed under section 8 of this act in response to such failures;

(4) a list of group homes that are exempt from compliance with the provisions of section 3 or 4 of this act, as provided by section 7 of this act;

(5) an indication of the number and percentage of private single occupancy rooms where electronic monitoring devices are installed and used, as provided by subsection b. of section 4 of this act, and the number and percentage of private double occupancy rooms where electronic monitoring devices are installed and used, as provided by subsection c. of section 4 of this act; and

(6) recommendations for legislative, executive, or other action that can be taken to improve compliance with the act's provisions or otherwise expand the consensual use of electronic monitoring devices in group homes.

c. The Ombudsman for Individuals with Intellectual or Developmental Disabilities and Their Families shall include, in each of the ombudsman's annual reports prepared pursuant to section 3 of P.L.2017, c.269 (C.30:1AA-9.3), a section evaluating the implementation of this act and providing recommendations for improvement.

10. The Commissioner of Human Services, in consultation with the assistant commissioner of the division, shall adopt rules and regulations, pursuant to the "Administrative Procedure Act," P.L.1968, c.410 (C.52:14B-1 et seq.), as may be necessary to effectuate the provisions of this act.

11. This act shall take effect on the 90th day following the date of enactment.

Daring a grocery trip with a profoundly autistic son

A mom must become a “special forces counter-insurgency specialist” to attempt some errands.

By Leanne Morphet

It's been about two and a half months since I dared venture to go into the store with ZMan. Yesterday, he asked so nicely to go, so I once again channeled my inner Brené Brown, chose to live bravely, and did a trip at 5:05 (yes, the start of after work rush hour) to Wally's World.

So what necessitates these feelings of not wanting to bring my beautiful boy into a store? My child exhibits aberrant and challenging behaviors that seem to come out of nowhere, frequently manifesting themselves at stores, culminating in various forms of (usually mild) property damage.

The current terminology we use to label the most prominent of these challenging behaviors is "dumping." Zach is not throwing with force, nor trying to break these items that he "dumps." The objects of these behaviors range in shape, size and form from paper bags (the most innocuous of things to dump) to eggs (who can forget the Great Tops Christmas Eve Egg Break of 2018) to a one-time encounter (thankfully) of a shelf of ceramic mugs at Michaels.

When I am on one of these trips with Zach — I am nothing short of a special forces counter-insurgency specialist, coming up with a comprehensive plan to simultaneously defeat and contain the behaviors and address its root causes.

This means I have had to cultivate a strategy to include determining if he is about to have an episode, informing those around me what is happening, handling any needed compensation for any irrevocable property damage, and, of course, all while having to dynamically develop a clear exit strategy. A true balancing act when contemplated solo — as I now do as a single parent.

We enter the store, I then consider every environmental factor we encounter filtered through what I understand of his specific sensory profile of what may cause him distress or undue attention, which seems to help, but certainly not always predict when he is ready to strike, and always ready for me to counter strike if he should decide or react to these things.

This is no time for Leanne to be doing the family grocery shopping — one distraction of a special on Baby Bella Mushrooms for Momma and *BAM*, Zach could be found throwing a cantaloupe (midfield if we were out at the stadium) clearly into the cruciferous vegetable section of the produce aisle.

The stunned look of our senior citizen shoppers as a bag of oyster crackers is turned into large pieces of fun shaped baked flour confetti in just an instant has sworn me off eye contact of all sorts because the last thing I need to be is distracted by another person's reactions when having to make sure the shrapnel of these episodes is contained and that Zach is safe.

Oh there is so much more to share but I will leave you with this feel-good moment: as I left the store with ZMan pushing the cart to our very sexy minivan — I did the quarterback's touchdown dance in the parking lot and high-fived my boy.

We had left the building and no, nosiree-bob, security was not called. #Victory #HellYeahAutism.

Leanne Boulware Morphet is an autism mom and advocate living in Central New York, and can be found occasionally recording her escapades at indomitablespiritgoddess.blogspot.com.